Link to Dagens Nyheter article (in Swedish)

October 18, 2023 – Towe Boström

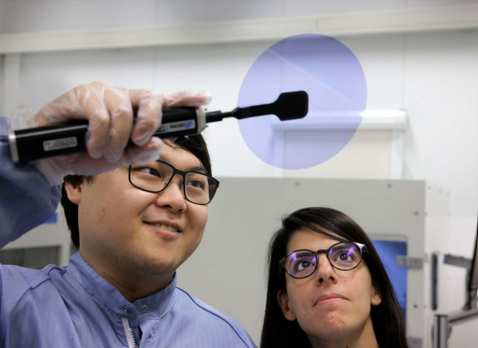

Paula Segura and David Dai show a wafer, the round disk of silicon carbide on which they apply gallium nitride through a patented technology in order to increase the efficiency of the transistors. Photo: Roger Turesson

Europe will invest hundreds of billions of kronor in its own production of the new, vital gold – the semiconductors.

In Sweden, new companies see their chance to gain ground – and it needs to happen quickly.

“AI will require an infinite number of chips, as will the automotive industry, where there are thousands of circuits in every car,” says Mikael Östling, professor of microelectronics at KTH.

U.S. President Joe Biden smiles at the camera. It’s the summer of 2022 when he signs the “Chips and Science Act” that will release hundreds of billions in order to spur the American semiconductor industry.

The investment comes after the hangover that arose in the wake of the pandemic when the world was paralyzed by the shortage of semiconductor components.

They can be found in everything from mobile phones to toasters and cars.

“Our entire society and economy is entirely based on semiconductor technology,” writes the Swedish Armed Forces, which calls it “the new gold” in a technical analysis from last year.

On the table in front of Jr-Tai Chen is the well-thumbed book “Chip War” by the American author Chris Miller, which describes the development of the market.

But the production chains are both costly and complex. The production of the most advanced chips, the kind that the tech giants want, has been dominated by Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturer TSMC.

It is a sensitive situation, both in terms of international dependence and the geopolitical uncertainty between Taiwan and China. At the same time, the U.S. continues to block China’s ability to import key technologies.

It is logical that more countries are tying semiconductor technology to them.

But Europe has only ten per cent of the market – a share that needs to be increased.

Jr-Tai Chen quickly weaves between craftsmen and machines in the large white room. Outside the window, the planes take off from Linköping Airport and in a few months the new semiconductor factory will be ready.

Jr-Tai Chen, here in the lab at Linköping University, where Swegan has another production facility.

“Speed is everything,” says Jr-Tai Chen, putting on blue plastic covers before heading into the next room where the new manufacturing machine is located.

It must not be photographed. The company Swegan wants to gain market share and the less its competitors know, the better.

It’s been 15 years since Jr-Tai Chen left his native Taiwan to study in Linköping. It was then that he invented and patented a special solution in the third-generation production of semiconductor materials, where the substance gallium nitride is applied in a thin layer to so-called wafers, round sheets of silicon carbide.

They are then acquired by customers who manufacture transistor components for microwave circuits and power circuits, which are used in defense technology, telecoms and electric vehicles, among other things.

Swegan has so far manufactured on a smaller scale at Linköping University, but will now increase the workforce from 20 to 40 people in its new factory before the end of the year.

At the same time, the EU has begun to flex its muscles. At the end of September, the new Chips Act entered into force, which aims to increase the Union’s share of the market from 10% to 20% by 2030.

“The semiconductor industry has been political and will become even more political in the future. In order for Swegan to succeed, we must manage the geopolitical changes that will affect the supply chains going forward.

The plan is to mobilise €43 billion from the public and private sectors to invest in both research and production.

It is this value chain that Swegan wants to be a part of.

But challenges remain.

Swegan was founded in 2014 at Linköping University and has recruited staff from a number of different countries. Photo: Roger Turesson

“We can’t win this alone, we have to work together a national strategy in Sweden, if there is one, it’s not clear to me,” says Jr-Tai Chen.

Mikael Östling, Professor of Microelectronics at KTH, notes that the world needs more and more crisps.

“AI will require an infinite amount of chips, as will the automotive industry, where there will be thousands of circuits in every car,” he says.

Mikael Östling believes that the 43 billion EU weight is not enough and calls for further collaboration between industry and education. He flags the need to train thousands of engineers and retrain already working people.

The company’s technology is used in 5G telecommunications infrastructure, satellite communications, and high-voltage power for devices such as electric vehicles. Photo: Roger Turesson

But he cannot foresee any large-scale production of semiconductors of the most advanced chips in the near future.

Such factories can cost hundreds of billions of dollars.

“It’s too far a step and we don’t have the skills for it. On the other hand, we have a strong opportunity to get the power manufacturers to establish themselves here.

Power semiconductors in particular are crucial for the electrification of society and do not require factories of as size.

“Sweden has a very strong tradition in the field and several startups,” says Mikael Östling.

Last year, Swegan had a turnover of more than SEK 11 million. At the same time, they made a loss of SEK 17 million, which is common for growth companies. The customers consist of some 20 players in Europe and the US, among other countries, and production will increase tenfold over the next six months.

Jr-Tai Chen says that he tried to attract Swedish investors a few years ago.

“They weren’t that familiar with semiconductors and the big investment funds weren’t that founder-friendly, unfortunately. Now we are waiting for major Swedish investors to take the lead and establish a semiconductor industry in Sweden.”

Jr-Tai Chen says that he tried to attract Swedish investors a few years ago. “They weren’t that familiar with semiconductors and the big investment funds weren’t that founder-friendly, unfortunately. Now we are waiting for major Swedish investors to take the lead and establish a semiconductor industry.”

Foto: Roger Turesson

“Our revenues will never be the highest in this sector, but we want to be known as a company that makes this manufacturing competitive and sustainable,” says Jr-Tai Chen.

However, the process of reaching larger volumes, and being approved by new customers, can take a few years.

And that requires both money and talent.

Swegan has raised SEK 125 million in venture capital from American, European, Taiwanese and Swedish investors and is advised by, among others, Ericsson’s former CEO Sven-Christer Nilsson.

A prerequisite for securing technology is that the companies stay in the country and are not bought up by foreign players. Swegan says it wants to avoid that and over 50 percent is owned by European owners, but they are asking for increased initiatives from the state.

“There’s a joke in Taiwain. If something falls from the sky on someone, that person has to work on something connected to semiconductors. That’s how high the chances are there, and I usually joke that semiconductors are floating in my blood,” says Swegan’s CEO Jr-Tai Chen, pictured here with Chief Operating Officer Henrik Tölander.

“We have to bring employees here and train them themselves, which is a long process. If Sweden and the EU are serious about investing and creating a chain for semiconductors, companies must be supported by the education system,” says Chief Operating Officer Henrik Tölander.

Adela Saavedra Granholm works in the field of industrial development at the Swedish innovation agency Vinnova.

“We don’t have time to wait 5-7 years. Efforts are needed for further training and we need robots for all these factories if we are to get going and achieve the goals,” she says.

Vinnova is a small cog in the big machine and they have applied to start one of the 27 planned European competence centers for semiconductors. In Sweden, the focus will be on small and medium-sized companies in research-related technology. Half of the funding will come from the EU and the other half from the country.

“This provides enormous opportunities for Sweden to attract investments, we need to get much better at it,” says Adela Saavedra Granholm.

Vinnova, which has an annual budget of SEK 50 million for the project, has provided documentation to get more money from the government.

She points to the importance of collaboration between large and small companies within the Union.

“It’s a way to find your way around Europe instead of someone from outside coming and buying them up.

The EU is also counting on private capital to step up at a time when the economy is being squeezed and investors are holding on tighter to capital.

Ted Persson is a partner at the European venture capital firm EQT, where he works with early technology investments.

“We have a lot of confidence that the US will solve it, but I think we also need to be in the game with new startups and manufacturing plans,” says Ted Persson.

Jr-Tai Chen, CEO of Swegan, which develops materials for semiconductors. Photo: Roger Turesson

In the Netherlands, there is ASML, which manufactures the machines that manufacture semiconductors. American Intel, and Taiwanese TSMC, are planning new factories in Germany, and in the UK, ARM is designing the chips for the world’s smartphones.

Ted Persson highlights Northvolt as a successful example of large-scale production in Sweden.

“Someone has to take the baton. It’s an incredibly large project and not many people have that perspective, but it would be very interesting,” says Ted Persson.

What will it take for Europe to reach the target of 20% of the market?

“Collaborative projects are required on a completely different level than what we have seen so far. Today, we often back one company early and then another investor backs that company and then we compete with each other. More collaboration between investors, universities and countries is now required.

Facts.Swegan

Swegan was founded in 2014 by Erik Janzén, Olof Kordina, and Jr-Tai Chen and has its roots in materials research at Linköping University. The company manufactures third-generation semiconductor materials and produces custom-made gallium nitride-on-silicon carbide (GaN-on-SiC) wafers. Swegan has patented a solution that makes the gallium nitride layer thinner, which increases performance. End customers include the defence industry, the space industry and telecom companies.

Facts.Semiconductors and the Chips Act

● Semiconductor materials are crystalline materials that do not conduct electric current as well as a conductor but also do not preclude conducting current as an insulator. The word semiconductor is used for both semiconductor materials, the diatoms on which the transistors are built, but also for the chip or semiconductor component.

● On September 21 this year, the Chips Act came into force. It will mobilise €43 billion in public and private funding to support semiconductor production and research in Europe. The global market share will increase from 10 to 20 percent by 2030. The U.S. has invested $52 billion in its counterpart.

● According to a survey by the industry organization Smarter Electronics Systems, the Swedish semiconductor industry consists of around 100 companies, most of which design and construct circuits that are manufactured by other players on the world market.

● Vinnova plans to finance the establishment of a semiconductor competence centre in Sweden, which is expected to start at the end of 2024 or beginning of 2025.